The lush, naturalist textile patterns, that Arne Jacobsen created in the 1940s, represent a different side of the famous modernist architect.

Arne Jacobsen’s patterns from the 1940s represent the voice of the artist and botanist, rather than the stringent modernist. With inspiration from free, naturalist plant motifs found in nature or in his lush garden, Arne Jacobsen created an original and personal expression.

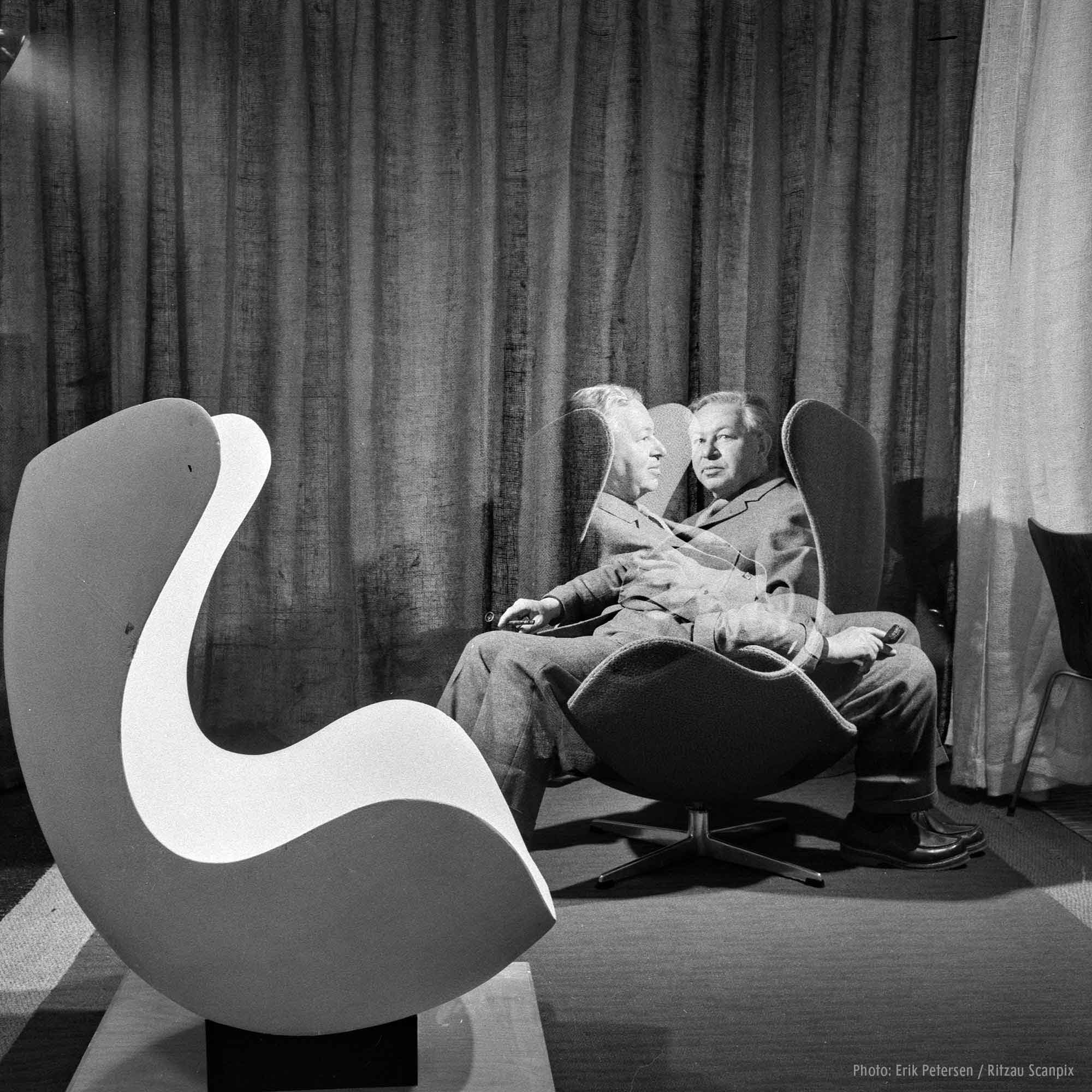

In autumn 1943, Arne Jacobsen had to flee and seek refuge in Sweden because the Nazis were intensifying their persecution of Jews in German-occupied Denmark. He fled across the Øresund strait in a rowing boat together with his wife, Jonna Jacobsen, and the designer and social critic Poul Henningsen and his wife. In Sweden, the young up-and-coming architect struggled to find work, so instead, Arne Jacobsen initiated a collaboration with the Stockholm department store Nordiska Kompaniet (Nordic Company), which had a production of fabrics and wallpapers by leading Nordic designers.

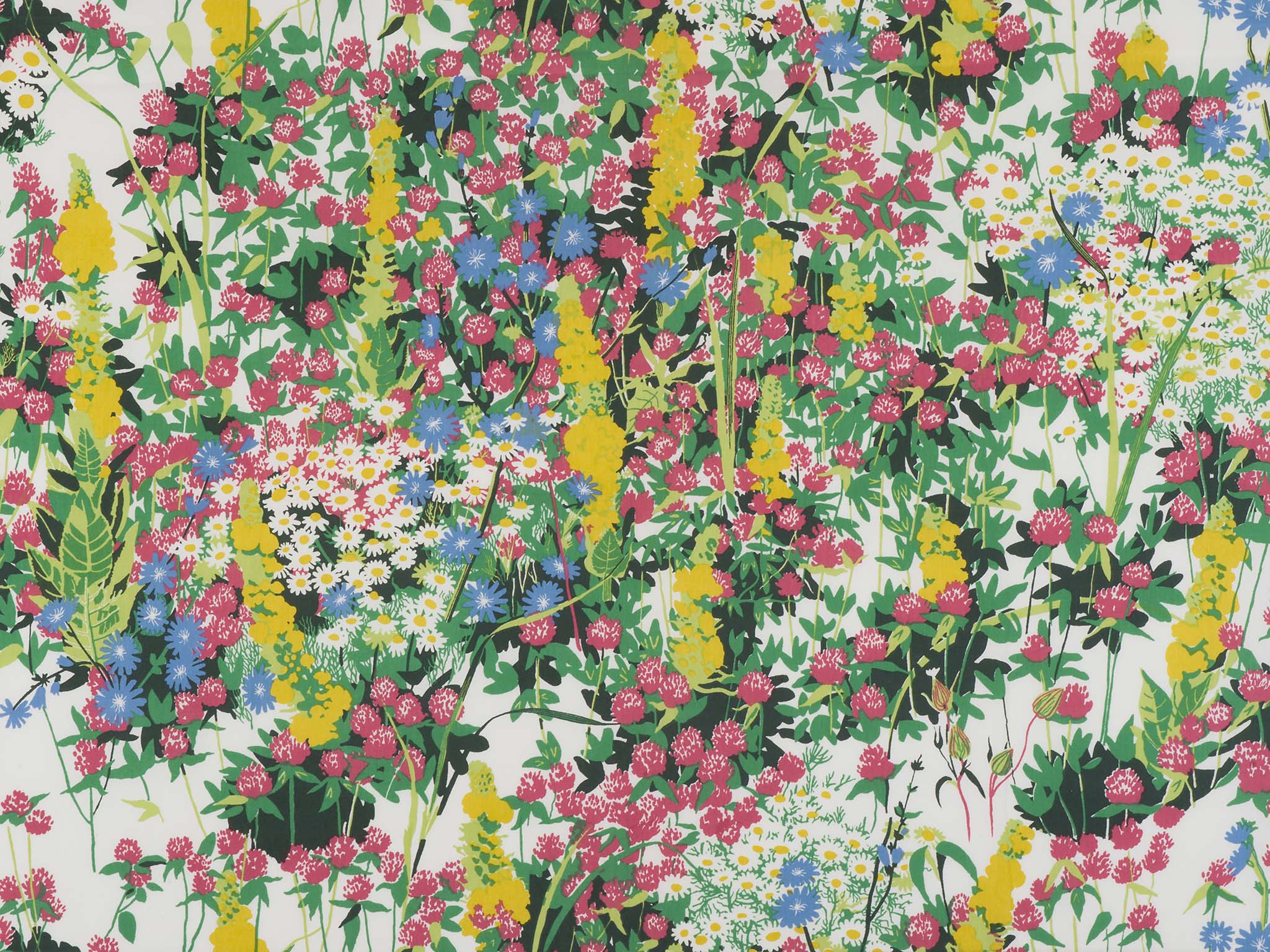

Before he left Denmark, Arne Jacobsen had begun to experiment with translating his drawings and watercolours into patterns that could be printed on textile. In 1942, Arne Jacobsen had met Jonna Jacobsen (née Møller) (1908-1995), who was a trained textile printer, and she probably helped him turn his nature studies into printable stencils. In spring 1943, they exhibited a series of printed textiles in the Charlottenborg Spring Exhibition – with Arne Jacobsen as designer and Jonna Jacobsen as printer. These patterns became the basis of the collection of 16 patterns that was presented by Nordiska Kompaniet in spring 1944 under the heading Handtryckta Textilier. Och därmed harmonierande tapeter (Hand-Printed Textiles. And Matching Wallpapers). The 16 patterns range from stylized and tightly composed patterns to free, naturalist motifs, where the entire surface is filled with exuberant plant life. In the wild plant environments in particular, Arne Jacobsen found an original, personal expression unlike other textile prints from the period.

The patterns show a different side of the famous designer and architect. This is not the voice of the modernist but rather that of the artist and botanist, and the motifs have a more private, sensitive, joy-filled feel. As a young man, Arne Jacobsen dreamt of becoming an artist, and throughout his life he painted charming watercolours of images from his lush garden, the landscape around his summer cottage at Gudmindrup Lyng or travels in France and Italy. Plants were an important source of inspiration to him: ‘If I had a second life, I would be a gardener,’ Arne Jacobsen often said and his passion for botany is evident in his watercolours and pattern designs. Arne Jacobsen’s biographer Johan Pedersen mentions how he met Arne Jacobsen seated in front of a large easel ‘in the middle of clover field’ at the summer cottage at Gudmindrup Lyng:

‘Surprisingly quickly, a section of the flowering field was captured on paper as a textile pattern. It was all instantaneously measured out at. The fresh nature impression was captured on paper with an exceptional sense of ease. This was not a chore but a celebration – a welcome break from the paper slavery of architectural design.’

In the wild plant environments in particular, Arne Jacobsen found an original, personal expression unlike other textile prints from the period.

When Arne Jacobsen returned to Denmark after the liberation in 1945, he continued to create new colourful patterns. He presented them in exhibitions on several occasions, including at the Museum of Art & Design (now Designmuseum Danmark) in Copenhagen together with sculptor Hugo Liisberg. They were also exported to Britain and the United States. Initially, the patterns were naturalist reproductions of lush nature, but towards the end of the decade, they became increasingly abstract. These latter designs point towards the strictly geometric patterns Arne Jacobsen designed during the 1950s and 1960s, when he was inspired more by modern art.

Initially, the patterns were naturalist reproductions of lush nature, but towards the end of the decade, they became increasingly abstract. These latter designs point towards the strictly geometric patterns Arne Jacobsen designed during the 1950s and 1960s, when he was inspired more by modern art.